If Walls Could Talk Home Is Where the Art Is

| نَيْنَوَىٰ | |

The reconstructed Mashki Gate of Nineveh (since destroyed by ISIL) | |

| Shown within Republic of iraq Show map of Republic of iraq Nineveh (Most East) Show map of Nearly East | |

| Location | Mosul, Nineveh Governorate, Republic of iraq |

|---|---|

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 36°21′34″Northward 43°09′10″Due east / 36.35944°N 43.15278°E / 36.35944; 43.15278 Coordinates: 36°21′34″Due north 43°09′ten″E / 36.35944°Due north 43.15278°E / 36.35944; 43.15278 |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | seven.5 km2 (ii.9 sq mi) |

| History | |

| Abased | 612 BC |

| Events | Boxing of Nineveh (612 BC) |

Nineveh (; Arabic: نَيْنَوَىٰ Naynawā ; Syriac: ܢܝܼܢܘܹܐ, romanized: Nīnwē ;[1] Akkadian: 𒌷𒉌𒉡𒀀 URUNI.NU.A Ninua ) was an aboriginal Assyrian city of Upper Mesopotamia, located on the outskirts of Mosul in modern-day northern Iraq. It is located on the eastern banking company of the Tigris River and was the uppercase and largest city of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, likewise equally the largest city in the globe for several decades. Today, it is a common name for the half of Mosul that lies on the eastern bank of the Tigris, and the country'south Nineveh Governorate takes its name from information technology.

Information technology was the largest metropolis in the globe for approximately 50 years[2] until the year 612 BC when, later a bitter period of civil war in Assyria, it was sacked past a coalition of its onetime subject area peoples including the Babylonians, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. The city was never again a political or administrative middle, but past Late Antiquity it was the seat of a Christian bishop. Information technology declined relative to Mosul during the Middle Ages and was mostly abandoned by the 13th century Advertisement.

Its ruins lie across the river from the modern-24-hour interval major city of Mosul, in Iraq's Nineveh Governorate. The two principal tells, or mound-ruins, within the walls are Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell Nabī Yūnus, site of a shrine to Jonah, the prophet who preached to Nineveh. Big amounts of Assyrian sculpture and other artifacts have been excavated at that place, and are at present located in museums around the world.

Proper noun [edit]

Artist's impression of Assyrian palaces from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853

The English placename Nineveh comes from Latin Nīnevē and Septuagint Greek Nineuḗ ( Νινευή ) under influence of the Biblical Hebrew Nīnəweh ( נִינְוֶה ),[iii] from the Akkadian Ninua (var. Ninâ)[4] or Old Babylonian Ninuwā .[3] The original significant of the proper noun is unclear only may have referred to a patron goddess. The cuneiform for Ninâ (𒀏) is a fish within a house (cf. Aramaic nuna, "fish"). This may have just intended "Place of Fish" or may accept indicated a goddess associated with fish or the Tigris, perchance originally of Hurrian origin.[four] The urban center was after said to be devoted to "the goddess Ishtar of Nineveh" and Nina was one of the Sumerian and Assyrian names of that goddess.[4]

Additionally, the word נון/נונא in Old Babylonian refers to the Anthiinae genus of fish,[5] farther indicating the possibility of an association between the proper noun Nineveh and fish.

The city was also known as Ninuwa in Mari;[iv] Ninawa in Aramaic;[4] Ninwe (ܢܸܢܘܵܐ) in Syriac;[ citation needed ] and Nainavā ( نینوا ) in Persian.

Nabī Yūnus is the Standard arabic for "Prophet Jonah". Kuyunjiq was, according to Layard, a Turkish name, and information technology was known as Armousheeah by the Arabs,[6] and is thought to accept some connection with the Kara Koyunlu dynasty.[7] These toponyms refer to the areas to the North and South of the Khosr stream, respectively: Kuyunjiq is the name for the whole northern sector enclosed by the city walls and is dominated by the large (35 ha) mound of Tell Kuyunjiq, while Nabī (or more commonly Nebi) Yunus is the southern sector around of the mosque of Prophet Yunus/Jonah, which is located on Tell Nebi Yunus.

Geography [edit]

Village in Nineveh in 2019

The remains of ancient Nineveh, the areas of Kuyunjiq and Nabī Yūnus with their mounds, are located on a level part of the obviously at the junction of the Tigris and the Khosr Rivers within an area of 750 hectares (1,900 acres)[8] circumscribed by a 12-kilometre (7.5 mi) fortification wall. This whole extensive infinite is now one immense area of ruins overlaid by c. one third past the Nebi Yunus suburbs of the city of eastern Mosul.[9]

The site of ancient Nineveh is bisected by the Khosr river. North of the Khosr, the site is called Kuyunjiq, including the acropolis of Tell Kuyunjiq; the illegal village of Rahmaniye lay in eastern Kuyunjiq. Due south of the Khosr, the urbanized surface area is called Nebi Yunus (too Ghazliya, Jezayr, Jammasa), including Tell Nebi Yunus where the mosque of the Prophet Jonah and a palace of Esarhaddon/Ashurbanipal beneath it are located. South of the street Al-'Asady (fabricated by Daesh destroying swaths of the city walls) the area is chosen Jounub Ninawah or Shara Pepsi.

Nineveh was an important junction for commercial routes crossing the Tigris on the great roadway between the Mediterranean Bounding main and the Indian Sea, thus uniting the E and the W, it received wealth from many sources, so that it became one of the greatest of all the region'southward aboriginal cities,[ten] and the last majuscule of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

History [edit]

Early history [edit]

Nineveh was one of the oldest and greatest cities in antiquity. Texts from the Hellenistic period later on offered an eponymous Ninus every bit the founder of Νίνου πόλις (Ninopolis), although in that location is no historical ground for this. Book of Genesis x:11 says "Nimrod", perhaps meaning Sargon I, congenital Nineveh. The context of Nineveh was as one of many centers within the regional development of Upper Mesopotamia. This area is defined as the plains which can support rain-fed agriculture. It exists as a narrow band from the Syrian coast to the Zagros mountains. Information technology is bordered by deserts to the south and mountains to the due north. The cultural practices, technology, and economy in this region were shared and they followed a similar trajectory out of the neolithic.

Neolithic [edit]

Caves in the Zagros Mountains side by side to the north side of the Nineveh Plains were used as PPNA settlements, most famously Shanidar Cavern. Nineveh itself was founded as early as 6000 BC during the late Neolithic period. Deep sounding at Nineveh uncovered soil layers that have been dated to early in the era of the Hassuna archaeological civilisation.[12] The development and culture of Nineveh paralleled Tepe Gawra and Tell Arpachiyah a few kilometers to the northeast. Nineveh was a typical farming village in the Halaf Menstruation.

Chalcolithic [edit]

In 5000 BC, Nineveh transitioned from a Halaf village to an Ubaid village. During the Late Chalcolithic period Nineveh was part ane of the few Ubaid villages in Upper Mesopotamia which became a proto-urban center Ugarit, Brak, Hamoukar, Arbela, Alep, and regionally at Susa, Eridu, Nippur. During the period betwixt 4500 and 4000 BC information technology grew to 40ha. The Ghassulians who migrated to Canaan circa 4800 BC came from the Zagros mountains to the immediate northeast of Nineveh, according to genetic studies.

The greater Nineveh area is notable in the diffusion of metal technology across the near east as the first location exterior of Anatolia to smelt copper. Tell Arpachiyah has the oldest copper smelting remains, and Tepe Gawa has the oldest metal work. The copper came from the mines at Ergani.

Early on Bronze Age [edit]

Nineveh became a trade colony of Uruk during the Uruk Expansion because of its location as the highest navigable bespeak on the Tigris. It was contemporary and had a similar function to Habuba Kabira on the Euphrates. By 3000 BC, Kish civilization had expanded into Nineveh. At this fourth dimension, the main temple of Nineveh becomes known every bit Ishtar temple, re-dedicated to the Semite goddess Ishtar, in the form of Ishtar of Nineveh. Ishtar of Nineveh was conflated with Šauška from the Hurro-Urartian pantheon. This temple was called 'House of Exorcists' (Cuneiform: 𒂷𒈦𒈦 GA2.MAŠ.MAŠ; Sumerian: e2 mašmaš).[13] [14] The context of the etymology surrounding the proper name is the Exorcist called a Mashmash in Sumerian, was a freelance magician who operated independent of the official priesthood, and was in part a medical professional via the human activity of expelling demons.

Ninevite five menstruum [edit]

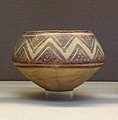

The regional influence of Nineveh became particularly pronounced during the archaeological period known as Ninevite 5, or Ninevite V (2900–2600 BC). This period is defined primarily past the characteristic pottery that is found widely throughout Upper Mesopotamia.[15] Also, for the Upper Mesopotamian region, the Early Jezirah chronology has been developed past archaeologists. Co-ordinate to this regional chronology, 'Ninevite 5' is equivalent to the Early Jezirah I–II period.[16]

Ninevite five was preceded past the Tardily Uruk menstruation. Ninevite 5 pottery is roughly contemporary to the Early Transcaucasian culture ware, and the Jemdet Nasr period ware.[fifteen] Iraqi Scarlet Ware culture also belongs to this period; this colourful painted pottery is somewhat similar to Jemdet Nasr ware. Scarlet Ware was get-go documented in the Diyala River basin in Iraq. Afterwards, it was besides found in the nearby Hamrin Bowl, and in Luristan. It is also contemporary with the Proto-Elamite menses in Susa.

- Styles Related to Ninevah v

-

Painted Jar - Ninevite 5

-

Painted bowl - Uruk-Nineveh 5 transition

-

Jemdet Nasr ware

-

Proto-Elamite ware 3100BC

-

Kura-Araxtes Culture

Late Statuary Historic period [edit]

At this time Nineveh was still an democratic city-state. It was incorporated into the Akkadian Empire. The early metropolis (and subsequent buildings) was constructed on a fault line and, consequently, suffered damage from a number of earthquakes. One such result destroyed the get-go temple of Ishtar, which was rebuilt in 2260 BC past the Akkadian king Manishtushu. After the fall of Ur in 2000 BC Nineveh was absorbed into the rising power of Assyria.

Former Assyrian flow [edit]

The historic Nineveh is mentioned in the Old Assyrian Empire during the reign of Shamshi-Adad I (1809-1775) in about 1800 BC equally a eye of worship of Ishtar, whose cult was responsible for the city's early importance.

Mitanni menstruation [edit]

Artist's impression of a hall in an Assyrian palace from The Monuments of Nineveh by Sir Austen Henry Layard, 1853

The goddess's statue was sent to Pharaoh Amenhotep III of Egypt in the 14th century BC, by orders of the rex of Mitanni. The Assyrian metropolis of Nineveh became 1 of Mitanni's vassals for half a century until the early on 14th century BC.

Middle Assyrian period [edit]

The Assyrian rex Ashur-uballit I reclaimed it in 1365 BC while overthrowing the Mitanni Empire and creating the Heart Assyrian Empire (1365–1050 BC).[17]

In that location is a big body of evidence to show that Assyrian monarchs built extensively in Nineveh during the late 3rd and 2d millenniums BC; information technology appears to accept been originally an "Assyrian provincial town". Later monarchs whose inscriptions have appeared on the high city include the Middle Assyrian Empire kings Shalmaneser I (1274–1245 BC) and Tiglath-Pileser I (1114–1076 BC), both of whom were agile builders in Assur (Ashur).

Iron Historic period [edit]

Neo-Assyrians [edit]

During the Neo-Assyrian Empire, specially from the fourth dimension of Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) onward, at that place was considerable architectural expansion. Successive monarchs such as Tiglath-pileser III, Sargon Two, Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal maintained and founded new palaces, every bit well as temples to Sîn, Ashur, Nergal, Shamash, Ninurta, Ishtar, Tammuz, Nisroch and Nabu.

Sennacherib'south development of Nineveh [edit]

Information technology was Sennacherib who fabricated Nineveh a truly magnificent urban center (c. 700 BC). He laid out new streets and squares and congenital within it the Due south West Palace, or "palace without a rival", the program of which has been generally recovered and has overall dimensions of about 503 past 242 metres (1,650 ft × 794 ft). It comprised at least eighty rooms, many of which were lined with sculpture. A large number of cuneiform tablets were institute in the palace. The solid foundation was fabricated out of limestone blocks and mud bricks; it was 22 metres (72 ft) tall. In total, the foundation is made of roughly two,680,000 cubic metres (iii,505,308 cu yd) of brick (approximately 160 million bricks). The walls on acme, made out of mud brick, were an additional twenty metres (66 ft) alpine.

Some of the principal doorways were flanked by colossal stone lamassu door figures weighing upward to 30,000 kilograms (30 t); these were winged Mesopotamian lions[xviii] or bulls, with human heads. These were transported 50 kilometres (31 mi) from quarries at Balatai, and they had to be lifted up 20 metres (66 ft) one time they arrived at the site, presumably by a ramp. In that location are likewise 3,000 metres (nine,843 ft) of stone Assyrian palace reliefs, that include pictorial records documenting every construction step including carving the statues and transporting them on a barge. One picture shows 44 men towing a colossal statue. The carving shows iii men directing the operation while continuing on the Colossus. Once the statues arrived at their destination, the terminal carving was washed. Most of the statues counterbalance between 9,000 and 27,000 kilograms (19,842 and 59,525 lb).[nineteen]

The stone carvings in the walls include many battle scenes, impalings and scenes showing Sennacherib'due south men parading the spoils of war before him. The inscriptions boasted of his conquests: he wrote of Babylon: "Its inhabitants, young and old, I did not spare, and with their corpses I filled the streets of the city." A full and feature set shows the campaign leading upwards to the siege of Lachish in 701; information technology is the "finest" from the reign of Sennacherib, and now in the British Museum.[20] He subsequently wrote about a battle in Lachish: "And Hezekiah of Judah who had not submitted to my yoke...him I shut up in Jerusalem his royal metropolis like a caged bird. Digging I threw up against him, and anyone coming out of his city gate I made pay for his criminal offence. His cities which I had plundered I had cut off from his state."[21]

At this time, the total expanse of Nineveh comprised near vii square kilometres (one,730 acres), and fifteen great gates penetrated its walls. An elaborate system of eighteen canals brought water from the hills to Nineveh, and several sections of a magnificently synthetic channel erected by Sennacherib were discovered at Jerwan, near 65 kilometres (40 mi) distant.[22] The enclosed expanse had more than than 100,000 inhabitants (maybe closer to 150,000), about twice as many as Babylon at the fourth dimension, placing it among the largest settlements worldwide.

Some scholars such every bit Stephanie Dalley at Oxford believe that the garden which Sennacherib built side by side to his palace, with its associated irrigation works, were the original Hanging Gardens of Babylon; Dalley'due south statement is based on a disputation of the traditional placement of the Hanging Gardens attributed to Berossus together with a combination of literary and archaeological evidence.[23]

Afterward Ashurbanipal [edit]

The walls of Nineveh at the fourth dimension of Ashurbanipal. 645-640 BC. British Museum BM 124938.[24]

The greatness of Nineveh was short-lived. In around 627 BC, after the death of its last peachy king Ashurbanipal, the Neo-Assyrian Empire began to unravel through a serial of bitter ceremonious wars betwixt rival claimants for the throne, and in 616 BC Assyria was attacked by its own onetime vassals, the Babylonians, Chaldeans, Medes, Persians, Scythians and Cimmerians. In most 616 BC Kalhu was sacked, the centrolineal forces eventually reached Nineveh, besieging and sacking the city in 612 BC, following bitter house-to-firm fighting, after which it was razed. Virtually of the people in the city who could not escape to the last Assyrian strongholds in the north and west were either massacred or deported out of the city and into the countryside where they founded new settlements. Many unburied skeletons were institute by the archaeologists at the site. The Assyrian Empire then came to an end by 605 BC, the Medes and Babylonians dividing its colonies between themselves.

It is not clear whether Nineveh came under the rule of the Medes or the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 612. The Babylonian Relate Concerning the Fall of Nineveh records that Nineveh was "turned into mounds and heaps", but this is literary hyperbole. The complete destruction of Nineveh has traditionally been seen as confirmed by the Hebrew Book of Ezekiel and the Greek Retreat of the Ten Thousand of Xenophon (d. 354 BC).[25] In that location are no subsequently cuneiform tablets in Akkadian from Nineveh. Although devastated in 612, the city was not completely abased.[25] Yet, to the Greek historians Ctesias and Herodotus (c. 400 BC), Nineveh was a thing of the past; and when Xenophon passed the place in the 4th century BC he described it every bit abandoned.[26]

Later history [edit]

The earliest piece of written testify for the persistence of Nineveh every bit a settlement is possibly the Cyrus Cylinder of 539/538 BC, but the reading of this is disputed. If correctly read as Nineveh, it indicates that Cyrus the Great restored the temple of Ishtar at Nineveh and probably encouraged resettlement. A number of cuneiform Elamite tablets accept been found at Nineveh. They probably date from the fourth dimension of the revival of Elam in the century post-obit the collapse of Assyria. The Hebrew Book of Jonah, Stephanie Dalley asserts was written in the fourth century BC, is an account of the metropolis's repentance and God's mercy which prevented destruction.[25]

Archaeologically, there is testify of repairs at the temple of Nabu after 612 and for the connected use of Sennacherib's palace. There is testify of syncretic Hellenistic cults. A statue of Hermes has been found and a Greek inscription attached to a shrine of the Sebitti. A statue of Herakles Epitrapezios dated to the 2nd century Advert has also been found.[25] The library of Ashurbanipal may still have been in apply until effectually the time of Alexander the Swell.[ contradictory ]

The city was actively resettled under the Seleucid Empire.[27] There is evidence of more changes in Sennacherib'due south palace under the Parthian Empire. The Parthians also established a municipal mint at Nineveh coining in bronze.[25] According to Tacitus, in Advert 50 Meherdates, a claimant to the Parthian throne with Roman back up, took Nineveh.[28]

By Late Antiquity, Nineveh was restricted to the east bank of the Tigris and the west bank was uninhabited. Under the Sasanian Empire, Nineveh was non an authoritative eye. By the 2nd century Advertisement there were Christians present and by 554 it was a bishopric of the Church building of the East. Male monarch Khosrow 2 (591–628) built a fortress on the w bank, and 2 Christian monasteries were constructed around 570 and 595. This growing settlement was not called Mosul until after the Arab conquests. Information technology may have been called Hesnā ʿEbrāyē (Jews' Fort).[27]

In 627, the metropolis was the site of the Battle of Nineveh between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Sasanians. In 641, it was conquered by the Arabs, who built a mosque on the west bank and turned information technology into an administrative centre. Under the Umayyad dynasty, information technology eclipsed Nineveh, which was reduced to a Christian suburb with limited new construction. By the 13th century, Nineveh was mostly ruins. A church was converted into a Muslim shrine to the prophet Jonah, which continued to concenter pilgrims until its destruction by ISIL in 2014.[27]

Biblical Nineveh [edit]

In the Hebrew Bible, Nineveh is showtime mentioned in Genesis ten:11: "Ashur left that land, and built Nineveh". Some modern English translations interpret "Ashur" in the Hebrew of this verse as the country "Assyria" rather than a person, thus making Nimrod, rather than Ashur, the founder of Nineveh. Sir Walter Raleigh'southward notion that Nimrod congenital Nineveh, and the cities in Genesis 10:11–12, has also been refuted by scholars.[29] The discovery of the fifteen Jubilees texts found amongst the Dead Ocean Scrolls, has since shown that, according to the Jewish sects of Qumran, Genesis ten:11 affirms the apportionment of Nineveh to Ashur.[30] [31] The attribution of Nineveh to Ashur is likewise supported past the Greek Septuagint, King James Bible, Geneva Bible, and past Historian Flavius Josephus in his Antiquities of the Jews (Antiquities, i, vi, 4).[32] [33] [34] [35] [ non-chief source needed ]

The Prophet Jonah before the Walls of Nineveh, drawing by Rembrandt, c. 1655

Nineveh was the flourishing majuscule of the Assyrian Empire[36] and was the dwelling of King Sennacherib, King of Assyria, during the Biblical reign of Male monarch Hezekiah (יְחִזְקִיָּהוּ) and the lifetime of Judean prophet Isaiah (ישעיה). As recorded in Hebrew scripture, Nineveh was also the place where Sennacherib died at the hands of his 2 sons, who and so fled to the vassal land of `rrt Urartu.[37] The volume of the prophet Nahum is almost exclusively taken up with prophetic denunciations against Nineveh. Its ruin and utter desolation are foretold.[38] [39] Its terminate was foreign, sudden, and tragic.[40] According to the Bible, it was God's doing, His judgment on Assyria's pride.[41] In fulfillment of prophecy, God fabricated "an utter stop of the place". It became a "pathos". The prophet Zephaniah also[42] predicts its devastation along with the fall of the empire of which it was the capital. Nineveh is also the setting of the Book of Tobit.

The Book of Jonah, set in the days of the Assyrian Empire, describes it[43] [44] as an "exceedingly great metropolis of 3 days' journey in breadth", whose population at that time is given as "more 120,000". Genesis 10:11-12 lists four cities "Nineveh, Rehoboth, Calah, and Resen", ambiguously stating that either Resen or Calah is "the great metropolis."[45] The ruins of Kuyunjiq, Nimrud, Karamlesh and Khorsabad form the four corners of an irregular quadrangle. The ruins of the "great urban center" Nineveh, with the whole area included inside the parallelogram they form by lines drawn from the one to the other, are generally regarded every bit consisting of these four sites. The description of Nineveh in Jonah likely was a reference to greater Nineveh, including the surrounding cities of Rehoboth, Calah and Resen[46] The Book of Jonah depicts Nineveh as a wicked city worthy of devastation. God sent Jonah to preach to the Ninevites of their coming destruction, and they fasted and repented because of this. As a result, God spared the city; when Jonah protests against this, God states He is showing mercy for the population who are ignorant of the difference betwixt correct and wrong ("who cannot discern betwixt their right manus and their left hand"[47]) and mercy for the animals in the city.

Nineveh'due south repentance and conservancy from evil can be found in the Hebrew Tanakh, aka the Old Attestation, and referred to in the Christian Bible and Muslim Quran.[48] To this mean solar day, Syriac and Oriental Orthodox churches commemorate the three days Jonah spent within the fish during the Fast of Nineveh. The Christians observing this holiday fast by refraining from food and drinkable. Churches encourage followers to refrain from meat, fish and dairy products.[49]

Archeology [edit]

The location of Nineveh was known, to some, continuously through the Centre Ages. Benjamin of Tudela visited it in 1170; Petachiah of Regensburg soon after.[50]

Carsten Niebuhr recorded its location during the 1761–67 Danish expedition. Niebuhr wrote subsequently that "I did not learn that I was at so remarkable a spot, till near the river. Then they showed me a hamlet on a not bad hill, which they call Nunia, and a mosque, in which the prophet Jonah was buried. Another hill in this commune is called Kalla Nunia, or the Castle of Nineveh. On that lies a village Koindsjug."[51]

Earthworks history [edit]

In 1842, the French Consul Full general at Mosul, Paul-Émile Botta, began to search the vast mounds that lay along the contrary bank of the river. While at Tell Kuyunjiq he had little success, the locals whom he employed in these excavations, to their groovy surprise, came upon the ruins of a building at the twenty km far-away mound of Khorsabad, which, on farther exploration, turned out to be the majestic palace of Sargon Ii, in which large numbers of reliefs were plant and recorded, though they had been damaged by burn and were generally likewise delicate to remove.

In 1847 the young British diplomat Austen Henry Layard explored the ruins.[52] [53] [54] [55] Layard did not use modern archaeological methods; his stated goal was "to obtain the largest possible number of well preserved objects of art at the least possible outlay of time and coin."[56] In the Kuyunjiq mound, Layard rediscovered in 1849 the lost palace of Sennacherib with its 71 rooms and colossal bas-reliefs. He besides unearthed the palace and famous library of Ashurbanipal with 22,000 cuneiform dirt tablets. Near of Layard'due south material was sent to the British Museum, but others were dispersed elsewhere as ii big pieces which were given to Lady Charlotte Invitee and eventually found their manner to the Metropolitan Museum.[57] The written report of the archæology of Nineveh reveals the wealth and glory of ancient Assyria under kings such as Esarhaddon (681–669 BC) and Ashurbanipal (669–626 BC).

The work of exploration was carried on past Hormuzd Rassam (an Assyrian), George Smith and others, and a vast treasury of specimens of Assyria was incrementally exhumed for European museums. Palace afterwards palace was discovered, with their decorations and their sculptured slabs, revealing the life and manners of this ancient people, their arts of war and peace, the forms of their religion, the style of their architecture, and the magnificence of their monarchs.[58] [59]

The mound of Kuyunjiq was excavated again by the archaeologists of the British Museum, led by Leonard William King, at the beginning of the 20th century. Their efforts full-bodied on the site of the Temple of Nabu, the god of writing, where another cuneiform library was supposed to exist. Yet, no such library was ever establish: most likely, information technology had been destroyed by the activities of later residents.

The excavations started again in 1927, nether the direction of Campbell Thompson, who had taken part in Rex's expeditions.[60] [61] [62] [63] Some works were carried out outside Kuyunjiq, for instance on the mound of Tell Nebi Yunus, which was the ancient arsenal of Nineveh, or along the exterior walls. Here, most the northwestern corner of the walls, beyond the pavement of a subsequently building, the archaeologists found near 300 fragments of prisms recording the royal annals of Sennacherib, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal, beside a prism of Esarhaddon which was almost perfect.

After the 2nd Globe State of war, several excavations were carried out by Iraqi archaeologists. From 1951 to 1958, Mohammed Ali Mustafa worked the site.[64] [65] The work was continued from 1967 through 1971 past Tariq Madhloom.[66] [67] [68] Some additional digging occurred by Manhal Jabur from the early 1970s to 1987. For the virtually part, these digs focused on Tell Nebi Yunus.

The British archaeologist and Assyriologist Professor David Stronach of the University of California, Berkeley conducted a series of surveys and digs at the site from 1987 to 1990, focusing his attentions on the several gates and the existent mudbrick walls, as well as the organisation that supplied h2o to the city in times of siege. The excavation reports are in progress.[69]

Most recently, an Iraqi-Italian Archaeological Expedition by the Alma Mater Studiorum - University of Bologna and the Iraqi SBAH, led past prof. Nicolò Marchetti, begun (with three campaigns having taken place thus far in the Fall between 2019 and 2021) a long-term projection aiming at the excavation, conservation and public presentation of Eastern Nineveh (NINEV_E project). Work was carried out in 11 earthworks areas, from the Adad Gate - now completely repaired (after removing hundreds of tons of debris from ISIL's destructions), explored and protected with a new roof - deep into the Nebi Yunus boondocks. In three areas a thick subsequently stratigraphy was encountered, just the late 7th century BC stratum was reached everywhere (really in two areas in the pre-Sennacherib lower boondocks the excavations already exposed older strata, up to the 11th-century BC until now, aiming in the future at exploring the showtime settlement therein). The site is profoundly endangered with dumping of debris, illegal settlements and quarrying as the main threats.

Archaeological remains [edit]

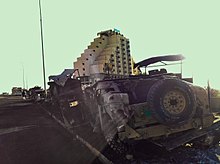

Humvee downward after ISIS assail

Today, Nineveh'due south location is marked past two large mounds, Tell Kuyunjiq and Tell Nabī Yūnus "Prophet Jonah", and the remains of the city walls (near 12 kilometres (7 mi) in circumference). The Neo-Assyrian levels of Kuyunjiq have been extensively explored. The other mound, Nabī Yūnus, has not been as extensively explored considering in that location was an Arab Muslim shrine dedicated to that prophet on the site. On July 24, 2014, the Islamic State of Republic of iraq and the Levant destroyed the shrine as part of a campaign to destroy religious sanctuaries it deemed "un-Islamic,"[70] but besides to loot that site through tunneling.

The ruin mound of Kuyunjiq rises virtually 20 metres (66 ft) in a higher place the surrounding plain of the ancient urban center. It is quite broad, measuring most 800 by 500 metres (2,625 ft × 1,640 ft). Its upper layers have been extensively excavated, and several Neo-Assyrian palaces and temples take been constitute at that place. A deep sounding by Max Mallowan revealed evidence of habitation as early as the 6th millennium BC. Today, at that place is little evidence of these old excavations other than weathered pits and earth piles. In 1990, the simply Assyrian remains visible were those of the entry court and the get-go few chambers of the Palace of Sennacherib. Since that time, the palace chambers have received significant damage past looters. Portions of relief sculptures that were in the palace chambers in 1990 were seen on the antiquities market by 1996. Photographs of the chambers fabricated in 2003 show that many of the fine relief sculptures there have been reduced to piles of rubble.

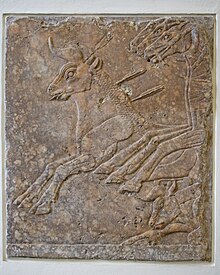

Winged Bull excavated at Tell Nebi Yunus by Iraqi archaeologists

Tell Nebi Yunus is located nigh one kilometre (0.half dozen mi) south of Kuyunjiq and is the secondary ruin mound at Nineveh. On the basis of texts of Sennacherib, the site has traditionally been identified every bit the "arsenal" of Nineveh, and a gate and pavements excavated by Iraqis in 1954 have been considered to be part of the "armory" complex. Excavations in 1990 revealed a monumental entryway consisting of a number of large inscribed orthostats and "bull-homo" sculptures, some apparently unfinished.

Post-obit the liberation of Mosul, the tunnels nether Tell Nebi Yunus were explored in 2018, in which a 3000-year-old palace was discovered, including a pair of reliefs, each showing a row of women, along with reliefs of lamassu.[71]

City wall and gates [edit]

Simplified programme of aboriginal Nineveh showing city wall and location of gateways

The ruins of Nineveh are surrounded past the remains of a massive rock and mudbrick wall dating from about 700 BC. About 12 km in length, the wall arrangement consisted of an ashlar rock retaining wall about 6 metres (twenty ft) high surmounted by a mudbrick wall about x metres (33 ft) high and fifteen metres (49 ft) thick. The stone retaining wall had projecting stone towers spaced near every xviii metres (59 ft). The stone wall and towers were topped by three-step merlons.

Five of the gateways have been explored to some extent by archaeologists:

- Mashki Gate (ماشکی دروازه)

Translated "Gate of the Water Carriers", (Mashki from Western farsi root word Mashk, meaning waterskin), also Masqi Gate (Standard arabic: بوابة مسقي),[72] it was perhaps used to take livestock to water from the Tigris which currently flows nigh 1.v kilometres (0.9 mi) to the west. It has been reconstructed in fortified mudbrick to the superlative of the peak of the vaulted passageway. The Assyrian original may have been plastered and ornamented. It was bulldozed along with the Adad Gate during ISIL occupation.[73]

- Nergal Gate

Named for the god Nergal, it may have been used for some ceremonial purpose, as it is the only known gate flanked past rock sculptures of winged bull-men (lamassu). The reconstruction is conjectural, as the gate was excavated by Layard in the mid-19th century and reconstructed in the mid-20th century. The lamassu on this gate were defaced with a jackhammer by ISIL forces.[74]

- Adad Gate

Photo of the restored Adad Gate, taken prior to the gate's destruction past ISIL in April 2016[73]

Adad Gate was named for the god Adad. A reconstruction was begun in the 1960s by Iraqis but was not completed. The result was a mixture of concrete and eroding mudbrick, which nonetheless does give some thought of the original structure. The excavator left some features unexcavated, allowing a view of the original Assyrian structure. The original brickwork of the outer vaulted passageway was well exposed, every bit was the entrance of the vaulted stairway to the upper levels. The deportment of Nineveh's last defenders could be seen in the hastily congenital mudbrick construction which narrowed the passageway from 4 to 2 metres (xiii to 7 ft). Around Apr 13, 2016, ISIL demolished both the gate and the adjacent wall past flattening them with a bulldozer.[75] [73]

- Shamash Gate

Named for the Sun god Shamash, information technology opens to the road to Erbil. It was excavated by Layard in the 19th century. The rock retaining wall and part of the mudbrick structure were reconstructed in the 1960s. The mudbrick reconstruction has deteriorated significantly. The rock wall projects outward nearly twenty metres (66 ft) from the line of main wall for a width of about seventy metres (230 ft). Information technology is the only gate with such a significant projection. The mound of its remains towers above the surrounding terrain. Its size and design advise it was the most of import gate in Neo-Assyrian times.

- Hali Gate

Near the south end of the eastern urban center wall. Exploratory excavations were undertaken here by the University of California, Berkeley expedition of 1989–1990. There is an outward projection of the city wall, though not as pronounced every bit at the Shamash Gate. The entry passage had been narrowed with mudbrick to nigh 2 metres (7 ft) equally at the Adad Gate. Human remains from the final battle of Nineveh were found in the passageway. [76] Located in the eastern wall, it is the southernmost and largest of all the remaining gates of ancient Nineveh.[72]

Threats to the site [edit]

Already in 2003, the site of Nineveh was exposed to decay of its reliefs by a lack of proper protective roofing, vandalism and annexation holes dug into bedchamber floors.[77] Future preservation is farther compromised by the site'due south proximity to expanding suburbs.

The bilious Mosul Dam is a persistent threat to Nineveh also as the city of Mosul. This is in no modest part due to years of disrepair (in 2006, the U.Due south. Army Corps of Engineers cited it every bit the well-nigh dangerous dam in the globe), the cancellation of a second dam project in the 1980s to deed as alluvion relief in case of failure, and occupation by ISIL in 2014 resulting in fleeing workers and stolen equipment. If the dam fails, the entire site could be under every bit much as 45 feet (xiv m) of h2o.[78]

In an October 2010 report titled Saving Our Vanishing Heritage, Global Heritage Fund named Nineveh one of 12 sites most "on the verge" of irreparable destruction and loss, citing insufficient management, development pressures and looting as principal causes.[79]

By far, the greatest threat to Nineveh has been purposeful human deportment by ISIL, which showtime occupied the surface area in the mid-2010s. In early 2015, they appear their intention to destroy the walls of Nineveh if the Iraqis tried to liberate the urban center. They as well threatened to destroy artifacts.[ citation needed ] On February 26 they destroyed several items and statues in the Mosul Museum and are believed to take plundered others to sell overseas. The items were more often than not from the Assyrian exhibit, which ISIL declared blasphemous and idolatrous. There were 300 items in the museum out of a total of 1,900, with the other 1,600 being taken to the National Museum of Iraq in Baghdad for security reasons prior to the 2014 Autumn of Mosul.[ according to whom? ] Some of the artifacts sold and/or destroyed were from Nineveh.[lxxx] [81] Simply a few days after the destruction of the museum pieces, they demolished remains at major UNESCO world heritage sites Khorsabad, Nimrud, and Hatra.

Rogation of the Ninevites (Nineveh's Wish) [edit]

Assyrians of the Ancient Church of the East, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church building, Syriac Orthodox Church, Assyrian Church of the East and Saint Thomas Christians of the Syro-Malabar Church detect a fast chosen Ba'uta d-Ninwe (ܒܥܘܬܐ ܕܢܝܢܘܐ) which means Nineveh'due south Prayer. Copts and Ethiopian Orthodox likewise maintain this fast.[82]

Popular civilisation [edit]

The English Romantic poet Edwin Atherstone wrote an ballsy The Fall of Nineveh.[83] The work tells of an insurgence against its rex Sardanapalus of all the nations that were dominated by the Assyrian Empire. He is a slap-up criminal. He has had one hundred prisoners of war executed. After a long struggle the boondocks is conquered by Median and Babylonian troops led by prince Arbaces and priest Belesis. The king sets his ain palace on fire and dies inside together with all his concubines.

John Martin, The Autumn of Nineveh

Atherstone'due south friend, the artist John Martin, created a painting of the same proper name inspired past the poem. The English language poet John Masefield'due south well-known, fanciful 1903 verse form Cargoes mentions Nineveh in its first line. Nineveh is besides mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's 1897 poem Recessional and in Arthur O'Shaughnessy's 1873 poem Ode.

The 1962 Italian peplum film, War Gods of Babylon, is based on the sacking and fall of Nineveh by the combined rebel armies led by the Babylonians.

In Jonah: A VeggieTales Film, Jonah must travel to Nineveh.

In the 1973 film The Exorcist Father Lankester Merrin was on an archeological dig about Nineveh prior to returning to the United States and leading the exorcism of Reagan MacNiel.

Meet as well [edit]

- Cities of the aboriginal Near Due east

- Destruction of cultural heritage by ISIL

- Historical urban community sizes

- Isaac of Nineveh

- List of megalithic sites

- Nanshe

- Curt chronology timeline

- Tel Keppe

Notes [edit]

- ^ Thomas A. Carlson et al., "Nineveh — ܢܝܢܘܐ " in The Syriac Gazetteer terminal modified June 30, 2014, http://syriaca.org/place/144.

- ^ Rosenberg, Matt T. "Largest Cities Through History". geography.about.com. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ a b Oxford English Lexicon, 3rd ed. "Ninevite, n. and adj." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 2013.

- ^ a b c d e "Nineveh", Encyclopaedia Judaica, Gale Group, 2008 .

- ^ Jastrow, Marcus (1996). A Dictionary of the Targumim, Talmud Babli, Talmud Yerushalmi and Midrashic Literature. NYC: The Judaica Printing, Inc. p. 888.

- ^ Layard, 1849, p.xxi, "...called Kuyunjiq by the Turks, and Armousheeah by the Arabs"

- ^ "Koyundjik", E. J. Brill'southward First Encyclopaedia of Islam, p. 1083 .

- ^ Mieroop, Marc van de (1997). The Ancient Mesopotamian City. Oxford: Oxford University Printing. p. 95. ISBN9780191588457.

- ^ Geoffrey Turner, "Tell Nebi Yūnus: The ekal māšarti of Nineveh," Iraq, vol. 32, no. 1, pp. 68–85, 1970

- ^ "Proud Nineveh" is an keepsake of earthly pride in the Old Testament prophecies: "And He will stretch out His hand against the north And destroy Assyria, And He volition make Nineveh a pathos, Parched similar the wilderness." (Zephaniah 2:thirteen).

- ^ Yard. E. L. Mallowan, "The Bronze Head of the Akkadian Period from Nineveh", Iraq Vol. iii, No. 1 (1936), 104–110.

- ^ Kuyunjiq / Tell Nebi Yunis (ancient: Nineveh) Archived 2020-11-05 at the Wayback Car colostate.edu

- ^ Lambert, W. (2004). "Ištar of Nineveh". Iraq. 66 (Papers of the 49th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale): 38. doi:10.1017/S0021088900001595. S2CID 163889444.

- ^ Gurney, O.R. (1936). "Keilschrifttexte nach Kopien von T. Thou. Pinches. Aus dem Nachlass veröffentlicht und bearbeitet". Rchiv Fiir Orientforschung. 11: 358–359.

- ^ a b Ian Shaw, A Dictionary of Archaeology. John Wiley & Sons, 2002 ISBN 0631235833 p427

- ^ Polish-Syrian Trek to Tell Arbid 2015

- ^ Genesis 10:11 attributes the founding of Nineveh to an Asshur: "Out of that land went forth Asshur, and builded Nineveh".

- ^ a b Ashrafian, H. (2011). "An extinct Mesopotamian lion subspecies". Veterinary Heritage. 34 (ii): 47–49.

- ^ "The Lxx Wonders of the Ancient Globe" edited by Chris Scarre 1999 (Thames and Hudson)

- ^ Reade, Julian, Assyrian Sculpture, pp. 56 (quoted), 65–71, 1998 (second edn.), The British Museum Printing, ISBN 9780714121413

- ^ Time Life Lost Civilizations series: Mesopotamia: The Mighty Kings. (1995)

- ^ Thorkild Jacobsen and Seton Lloyd, Sennacherib's Aqueduct at Jerwan, Oriental Institute Publication 24, University of Chicago Press, 1935

- ^ Dalley, Stephanie (2013). The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon: an elusive Globe Wonder traced. Oxford University Printing. ISBN978-0-19-966226-5.

- ^ "Wall console; relief British Museum". The British Museum.

- ^ a b c d due east Stephanie Dalley (1993), "Nineveh after 612 BC", Altorientalische Forschungen 20(1): 134–147.

- ^ Menko Vlaardingerbroek (2004), "The Founding of Nineveh and Babylon in Greek Historiography", Iraq, vol. 66, Nineveh. Papers of the 49th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Function One, pp. 233–241.

- ^ a b c Peter Webb, "Nineveh and Mosul", in O. Nicholason (ed.), The Oxford Lexicon of Late Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 2018), vol. two, p. 1078.

- ^ J. Due east. Reade (1998), "Greco-Parthian Nineveh", Iraq sixty: 65–83.

- ^ Shuckford, Samuel; James Talboys Wheeler (1858), The sacred and profane history of the world connected, vol. i, pp. 106–107

- ^ "Jubilees 9". www.pseudepigrapha.com . Retrieved 17 November 2017.

- ^ VanderKam, "Jubilees, Book of" in L. H. Schiffman and J. C. VanderKam (eds.), Encyclopedia of the Dead Body of water Scrolls, Oxford University Printing (2000), Vol. I, p. 435.

- ^ Greek Septuagint.

- ^ Geneva Bible.

- ^ 1611 King James Bible.

- ^ New Rex James Version.

- ^ two Kings 19:36

- ^ Isa. 37:37–38

- ^ Nahum 1:14

- ^ Nahum 3:19

- ^ Nahum ii:6–11

- ^ Isaiah x:5–19

- ^ Zephaniah ii:13–15

- ^ Jonah 3:3

- ^ Jonah 4:11

- ^ Genesis 10:11–12

- ^ The NIV study Bible. Barker, Kenneth Fifty., Burdick, Donald W. (tenth ceremony ed.). Chiliad Rapids, MI: Zondervan Pub. Business firm. 1995. p. 1361. ISBN0-310-92568-1. OCLC 33344874.

{{cite volume}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Jonah iv / Hebrew - English language Bible / Mechon-Mamre". www.mechon-mamre.org.

- ^ Also see these scriptural references: Gospel of MatthewMatthew 12:41, Gospel of LukeLuke eleven:32 and Quran (37:139-148)

- ^ "Three Day Fast of Nineveh". Syrian Orthodox Church building. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved i February 2012.

- ^ Liverani 2016, p. 23. "Toward 1170 the rabbi Benjamin of Tudela, who was traveling throughout the Virtually East passing from 1 Hebrew community to another, having arrived at Mosul (which he called 'Assur the Slap-up') had a articulate idea (thanks to data given to him by his local colleagues) that across the Tigris was the famous Ninevah, in ruins simply covered with villages and farms [...] Ten years later another rabbi, Petachia of Ratisbon, as well arriving at Mosul (which he called the 'New Ninevah') and crossing the river, visited 'Old Ninevah', which he described equally desolate and 'overthrown like Sodom' with the land black like pitch, without a bract of grass. [...] Myths apart, the localization of Ninevah remained a matter of common knowledge and beyond argument; various western travelers (such equally Jean Baptiste Tavernier in 1644, so Bourguignon d'Anville in 1779) confirmed information technology, and some soundings followed."

- ^ Pusey, Edward Bouverie (1888), The Minor Prophets, with a Commentary, Explanatory and Practical, and Introductions to the Several Books, Book II, p.123

- ^ A. H. Layard, Nineveh and Its Remains, John Murray, 1849

- ^ A. H. Layard, Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, John Murray, 1853

- ^ A. H. Layard, The Monuments of Nineveh; From Drawings Made on the Spot, John Murray, 1849

- ^ A. H. Layard, A second series of the monuments of Nineveh, John Murray, 1853

- ^ Liverani 2016, pp. 32–33.

- ^ John Malcolm Russell, From Nineveh to New York: The Foreign Story of the Assyrian Reliefs in the Metropolitan Museum & the Hidden Masterpiece at Canford School, Yale University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-300-06459-4

- ^ George Smith, Assyrian Discoveries: An Account of Explorations and Discoveries on the Site of Nineveh, During 1873 and 1874, S. Depression-Marston-Searle and Rivington, 1876

- ^ Hormuzd Rassam and Robert William Rogers, Asshur and the Land of Nimrod, Curts & Jennings, 1897

- ^ R. Campbell Thompson and R. W. Hutchinson, "The excavations on the temple of Nabu at Nineveh," Archaeologia, vol. 79, pp. 103–148, 1929

- ^ R. Campbell Thompson and R. Westward. Hutchinson, "The site of the palace of Ashurnasirpal 2 at Nineveh excavated in 1929–30," Liverpool Annals of Archeology and Anthropology, vol. 18, pp. 79–112, 1931

- ^ R. Campbell Thompson and R. W. Hamilton, "The British Museum excavations on the temple of Ishtar at Nineveh 1930–31," Liverpool Register of Archaeology and Anthropology, vol. 19, pp. 55–116, 1932

- ^ R. Campbell Thompson and Grand E Fifty Mallowan, "The British Museum excavations at Nineveh 1931–32," Liverpool Annals of Archaeology and Anthropology, vol. 20, pp. 71–186, 1933

- ^ Mohammed Ali Mustafa, Sumer, vol. 10, pp. 110–eleven, 1954

- ^ Mohammed Ali Mustafa, Sumer, vol. 11, pp. iv, 1955

- ^ Tariq Madhloom, Excavations at Nineveh: A preliminary study, Sumer, vol. 23, pp. 76–79, 1967

- ^ Tariq Madhloom, Excavations at Nineveh: The 1967–68 Campaign, Sumer, vol 24, pp. 45–51, 1968

- ^ Tariq Madhloom, Excavations at Nineveh: The 1968–69 Campaign, Sumer, vol. 25, pp. 43–49, 1969

- ^ "Shelby White – Leon Levy Program for Archaeological Publications – Nineveh Publication Grant". Archived from the original on 2011-07-22. Retrieved 2011-05-16 .

- ^ "Officials: ISIS blows upwards Jonah'due south tomb in Iraq". CNN.com. 2014-07-24. Retrieved 2014-07-24 .

- ^ "Explore the IS Tunnels". BBC News. 22 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Gates of Nineveh". Madain Projection . Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Romey, Kristin (19 April 2016), "Exclusive Photos Show Destruction of Nineveh Gates by ISIS", National Geographic, The National Geographical Society

- ^ "ISIS 'bulldozed' ancient Assyrian metropolis of Nimrud, Republic of iraq says". Rappler. March 5, 2015. Retrieved July vii, 2020.

- ^ "Iraqi Digital Investigation Team Confirms ISIS Destruction of Gate in Nineveh". Bellingcat. Baronial 29, 2016. Retrieved August xxx, 2016.

- ^ Diana Pickworth, Excavations at Nineveh: The Halzi Gate, Iraq, vol. 67, no. 1, Nineveh. Papers of the 49th Rencontre Assyriologique Internationale, Part Two, pp. 295–316, 2005

- ^ "Cultural Assessment of Iraq: The State of Sites and Museums in Northern Iraq – Nineveh". National Geographic News. May 2003.

- ^ Borger, Julian (two March 2016). "Mosul dam engineers warn information technology could fail at any time, killing 1m people". The Guardian. guardian.co.united kingdom. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- ^ "Globalheritagefund.org". Archived from the original on August 20, 2012.

- ^ "Iraq: Isis militants pledge to destroy remaining archaeological". The Contained. Feb 27, 2015.

- ^ "ISIL video shows destruction of 7th century artifacts". america.aljazeera.com.

- ^ Warda, W, Christians of Iraq: Ba-oota d' Ninevayee or the Fast of the Ninevites, re-accessed 11 September 2016

- ^ Herbert F. Tucker, Epic. Britain's Heroic Muse 1790–1910, Oxford University Press, Oxford 2008, p. 256-261.

References [edit]

-

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Nineveh". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain:Easton, Matthew George (1897). "Nineveh". Easton's Bible Dictionary (New and revised ed.). T. Nelson and Sons.

-

- Russell, John Malcolm (1992), Sennacherib'due south "Palace without Rival" at Nineveh, University Of Chicago Press, ISBN0-226-73175-viii

- Barnett, Richard David (1976), Sculptures from the north palace of Ashurbanipal at Nineveh (668-627 B.C.), British Museum Publications Ltd, ISBN0-7141-1046-ix

- Campbell Thompson, R.; Hutchinson, R. West. (1929), A century of exploration at Nineveh, Luzac

- Bezold, Carl, Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Drove of the British Museum

- Volume I, 1889

- Book II, Printed by order of the Trustees, 1891

- Volume III, 1893

- Book IV, 1896

- Book V, Printed by order of the Trustees, 1899

- Catalogue of the Cuneiform Tablets in the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum, British Museum

- King, Due west. 50. (1914), Supplement I

- Lambert, West. G. (1968), Supplement II

- Lambert, Due west. M. (1992), Supplement III, ISBN0-7141-1131-7

- Liverani, Mario (2016) [2013], Immaginare Babele [Imagining Babylon: The Modern Story of an Aboriginal City], translated by Campbell, Alisa, De Gruyter, ISBN978-1-61451-602-6

- Scott, M. Louise; MacGinnis, John (1990), Notes on Nineveh, Iraq, vol. 52, pp. 63–73

- Trümpler, C., ed. (2001), Agatha Christie and Archeology, The British Museum Press, ISBN978-0714111483 - Nineveh 5, Vessel Pottery 2900 BC

- Leick, Gwendolyn (2010), The A to Z of Mesopotamia, Scarecrow Printing - Early worship of Ishtar, Early on / Prehistoric Nineveh

- Durant, Will (1954), Our oriental heritage, Simon & Schuster – Early / Prehistoric Nineveh

External links [edit]

| | Look up Nineveh in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nineveh. |

- Joanne Farchakh-Bajjaly photos of Nineveh taken in May 2003 showing damage from looters

- John Malcolm Russell, "Stolen stones: the modern sack of Nineveh" in Archaeology; looting of sculptures in the 1990s

- Nineveh page Archived 2015-09-26 at the Wayback Machine at the British Museum's website. Includes photographs of items from their collection.

- University of California Digital Nineveh Archives A didactics and research tool presenting a comprehensive motion picture of Nineveh within the history of archaeology in the Well-nigh E, including a searchable information repository for meaningful analysis of currently unlinked sets of information from different areas of the site and different episodes in the 160-year history of excavations

- CyArk Digital Nineveh Archives, publicly attainable, costless depository of the data from the previously linked UC Berkeley Nineveh Archives project, fully linked and georeferenced in a UC Berkeley/CyArk research partnership to develop the archive for open web apply. Includes artistic commons-licensed media items.

- Photos of Nineveh, 1989–1990

- ABC 3 Archived 2016-xi-10 at the Wayback Machine: Babylonian Chronicle Concerning the Fall of Nineveh

- Layard'southward Nineveh and its Remains- full text

0 Response to "If Walls Could Talk Home Is Where the Art Is"

Postar um comentário